Shakespeare in Ten Acts

An exhibition at the British Library

15 April to 6 September 2016, the British Library, London

Review by Gemma Miller, PhD Candidate, English

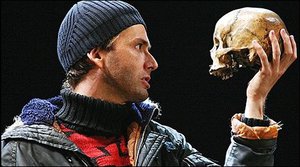

Tennant with Tchaikowsky's skull

This exciting exhibition looks at ten landmark performances across the 400-year history of Shakespeare’s plays, from the first stagings of Hamlet in 1600 at the newly-constructed Globe theatre to the Wooster Group’s postmodern, multi-media pastiche of Hamlet at the Edinburgh Festival in 2013.

What makes this particular exhibition unique is the way in which it focuses on how Shakespeare has been constructed and reconstructed to suit the purposes of each generation. In this respect, it is a particularly illuminating insight into the processes of cultural appropriation. There are, as would be expected, some rare Elizabethan manuscripts that offer tantalising insights into Shakespeare’s character. One particularly vivid example is the 1602 diary entry from law student John Manningham. He recounts a story about how Shakespeare stole an invitation to meet a female fan after a performance of Richard III at the Globe that was meant for its star, Richard Burbage. According to Manningham’s diary, when Burbage arrived at the lady’s lodgings, he received a message from his fellow-player saying ‘William the Conqueror was before Richard the 3’.

This manuscript is displayed alongside other less salacious but more historically-verifiable glimpses into Shakespeare: a copy of Sir Thomas More, the only surviving play-script in Shakespeare’s hand; one of six authentic Shakespeare signatures; and one of four surviving First Folios to feature the first state of the Martin Droeshout portrait. However, as Eric Rasmussen observes in his ‘Prologue’ to the exhibition book, in spite of these beguiling snippets of documented evidence, ‘one may well continue to feel that we do not have a handle on the real man.’

This is, however, of little concern in this particular exhibition. The items of real interest are those that provide a handle on the ‘Shakespeare’ we have appropriated and fashioned to suit our purposes throughout the ages. A history of key Hamlet productions, for instance, reveals a morbid fascination with Yorick’s skull that transcends generations. On display is the human skull presented by Victor Hugo to the French actress Sarah Bernhardt which she used in the graveyard scene in her gender-blind performances in 1899.

Beside this are images of David Tennant in Gregory Doran’s 2007-8 production of Hamlet for the RSC, holding a skull bequeathed by concert pianist Andre Tchaikowsky. When this particular skull threatened to upstage the performance of Doran’s leading man, he announced that it was being replaced with a replica, only to admit at the end of the production run that it had been real all along.

Posters, storyboards, scripts, props, costumes, paintings and infamous forgeries (step forward, William Henry Ireland) sit cheek by jowl with recordings and films of some of the most seminal performances of the plays. Highlights include the storyboard from Laurence Olivier’s film of Henry V (1944); Titania’s swing from Peter Brook’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1970); the tiny, heavily-corsetted costume worn by Mark Rylance as Olivia in his ‘Original Practices’ Twelfth Night (2002); and the chance to compare nine audio versions of ‘To be or not to be’, from Herbert Beerbohm Tree in 1906 to David Tennant in 2013, via Laurence Olivier (1949), Kenneth Branagh (1988) and Simon Russell Beale (2000). With over 200 items on display, this is an exhibition in which everybody will be able to find the Hamlet, and the ‘Shakespeare’, that resonates most personally with them.