Ben Jonson’s Masque of Queens

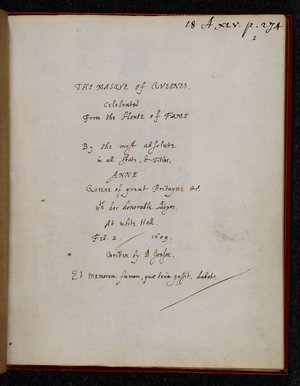

The Masque of Queens, by Ben Jonson and Inigo Jones.

Directed by Dr Emma Whipday and performed 11 August 2016 at New College Chapel, Oxford.

Blog post by Dr Daniel Starza Smith, Lecturer in Early Modern English Literature (1500-1700)

Ben Jonson (11 June 1572–6 August 1637) was one of the seventeenth-century’s most influential literary figures. Best known as a prolific and combative dramatist, poet, and literary critic, he was also famously a soldier, murderer, scandal-monger, reluctant bricklayer, classicist, glutton, and drinker. His friend William Drummond called him: ‘a great lover and praiser of himself, a contemnor and scorner of others, given rather to lose a friend than a jest, jealous of every word and action of those about him (especially after drink, which is one of the elements in which he liveth).’ Arrested and tortured for the seditious content of his early plays, he was later suspected as a Gunpowder Plot conspirator.

Within his lifetime and in the century following his death, Jonson was regarded by many as the greatest of all English authors, living or dead. Although this is hardly believable today, in his own day his fame surpassed even that of his friend and rival, William Shakespeare. While we commemorate Shakespeare’s momentous cultural value in 2016, let us thus spare a thought for Ben Jonson – who would have been outraged to take a supporting role in the celebrations.

2016 marks the quatercentenary anniversary of Jonson’s Workes, a pioneering volume in the history of literature and printing, and a precursor to the 1623 Shakespeare First Folio. It was considered highly presumptuous for an author to collect his own works together in a single folio volume, a format usually reserved for the ‘classics’ of antiquity. Along with The Works of Samuel Daniel (1601) and Works of Edmund Spenser (1611) Jonson’s volume created conceptual space in the literary marketplace for the collected writings of a contemporary author. Yet its ornate frontispiece indicates the key difference – here we see tragoedia and comoedia standing above emblematic representations of the theatre. By aligning drama with the opera of classical authors, the Workes directly anticipates the Shakespeare First Folio.

To celebrate Jonson’s achievements, Nadine Akkerman (University of Leiden) and I decided to stage one of his court masques, The Masque of Queens alongside an exhibition at the Bodleian Library (‘O Rare Ben Jonson!’), as part of a two-day conference on his influential patron Lucy Harington Russell, Countess of Bedford, who danced in the masque’s first performance in 1609. We had the ideal director in mind, Emma Whipday, then at King’s (now a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at UCL), and soon after she accepted our invitation we were granted permission to use the exceptionally beautiful chapel at New College, Oxford.

The Masque of Queens was originally conceived as a music, dance, and fashion spectacle as well as a theatrical text. Partially designed by architect Inigo Jones, it depicts 12 virtuous queens conquering the disruptive forces of 12 troublemaking witches. The first staging featured courtiers and royals in the starring roles, including a notable performance by Lady Bedford, and would have involved two dozen actors plus many musicians. Whipday presented a slightly edited text, and deployed six actors, mostly students from King’s MA degrees in Shakespeare Studies and Early Modern English Literature: Text and Transmission. After the dramatic performance, professional dancers Mary Collins, Anne Deller, and Steven Player emerged from the antechapel into the main nave, accompanied by professional musicians Alison Kinder, Sharon Lindo, and Richard MacKenzie. We were treated to a rare and fine performance of early modern dance.

The masque was free, but ticketed; all 200 tickets went within 48 hours, making it all the more important that the masque was recorded. We hope that the video will become a useful resource for teachers of masques, and that it will attract the attention of musicians and dancers as well as actors and directors.

Whipday summarized the importance of the masque as follows: ‘As a director of rarely performed early modern plays, I found that Masque of Queens represented a unique challenge: an “original practice” production of an early modern masque is near-impossible, and so this project involved a combination of contemporary theatrical tools and historically informed performance. I wanted to experiment with treating the masque as a contemporary performance text, inviting the audience to step back in time to King James’s court, whilst reimagining the gender dynamics of that time, in keeping with the masque’s interest in powerful and transgressive women. We reimagined the division between professional (male) actors playing witches and amateur noblewomen playing queens, by using the conceit that all roles, including witches, queens, Fame, and Heroic Virtue, were played by female noblewomen; and followed the anti-masque and masque with performances by professional dancers, in a gesture towards the dancing that was a key element of court entertainments. The production was in some sense ‘site-specific’, enabling us to play on the dramatic period features (and, of course, the religious resonances) of New College Chapel in first staging the dangerous irreverence of the witches, and then, in using the architecture of the chapel – specifically its giant, illuminated reredos – to create an alternative vision of Inigo Jones’s House of Fame.’

She continues: ‘The technical challenges, in approaching the witches’ and queens’ dances, and in rehearsing the long speeches with relatively few indications of action, were considerable; and the opportunity our funders have given us to work with a physical theatre practitioner and a historical dance specialist was invaluable in meeting these challenges. The experience as a whole provided multiple learning opportunities for the cast, a mix of MA students at King’s, and an education assistant at Shakespeare’s Globe; they were able to draw on, and deepen, their knowledge of masque culture, while learning technical skills in theatre and dance that enriched their own creative practice. The roles of the witches and the queens contain give little clues as to what we now think of as ‘character’ or ‘motivation’, which represented a challenge for a cast of amateur actors, many of whom had some form of dramatic training, and who were used to a post-Stanislavian approach to performance. We therefore involved other MA students and PhD candidates in the rehearsal process, drawing on their expertise to enable the actors to imagine themselves as specific early modern noblewomen performing witches and queens, providing a “way in” to these roles.’

Nadine Akkerman added that ‘The masque was important to me as a scholar because – even though I have been writing on and teaching the form for a decade now – I had never seen one performed. This online video will be a great tool to be able to show students how these seemingly flimsy texts come alive. Hearing Jonson’s words being spoken – words written by a major canonical author but silenced for centuries – was a reminder of how well his rhythmic verses worked on stage, and we experienced first-hand how an audience could almost be hypnotized by the witches. To have it staged in a physical space that resembled Banqueting Hall brought out the challenges of actors interacting with space, acoustics and audiences.’

The masque was funded by The OUP John Fell Fund at the University of Oxford and The Ludwig Fund for the Arts at New College. The video recording was substantially funded by the Malone Society.