Julius Caesar (1953)

Shakespeare on Film: Screening of Julius Caesar (1953, Dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz)

BFI Southbank

Friday 1 April 2016

Review by Jenna Byers, PhD candidate, History

With any production of Julius Caesar, the casting of the eponymous Caesar is of less importance than that of other characters. Central to the feel and experience of the play, or in this case the film, is the casting of Brutus and Mark Antony. In this 1953 production, Brutus is played by James Mason, who is something of an unusual choice for Brutus. His acting style is so languorous it is sometimes hard to believe he has the energy to walk to the Senate in the morning, never mind go to war in the latter half of the film.

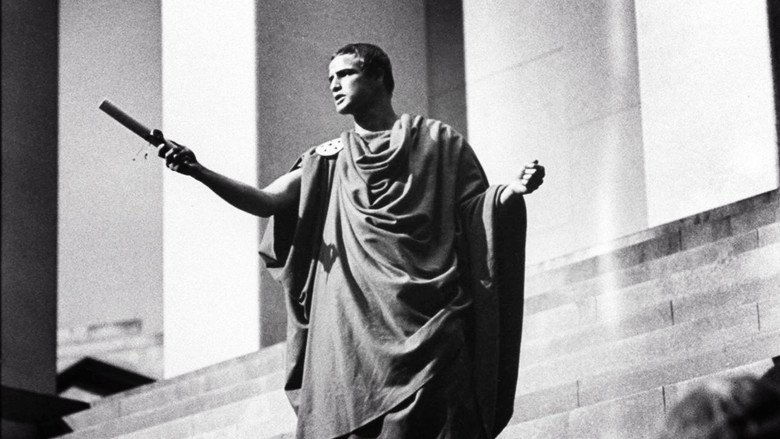

Marlon Brando as Mark Antony in Julius Casear (1953)

Mark Antony, on the other hand, is presented as a fiery,

wilful young man whose speech at Caesar’s funeral was almost

powerful enough to rouse the audience in the cinema from our

seats. Mark Antony is played by Marlon Brando, a decision

which the studio originally opposed, but which turned out to

be an astute move on the part of the producers, as his youth

and fire prove a perfect counterfoil to the more sanguine

nature of his opponents in the piece.

However, the real star of the film is Cassius, played by John Gielgud. Largely unnoticed in other productions I have seen, in this film he is electric, and essential to the piece, controlling the pace of the story. Even those who have seen Julius Caesar plenty of times before will find something to take away from this performance.

The production is, of course, somewhat dated. It was made in a time when the limits of special and visual effects drastically reduced the scope of what cinema could achieve, and thus it is a fairly straightforward adaptation from stage to screen. This does not, by any means, make it a bad film. In fact, this is an adaptation which cuts straight to the centre of Shakespeare’s story, focusing on the theme of power and how to hold it once you’ve earned it, themes with enduring relevance to this day. Some of the dialogue has been cut to trim the length, leaving a film which is very much plot-driven, and the film does not linger in the way that some adaptations of Shakespeare’s work have been known to do.

The movie was shot in black and white, on sets of simple designs which allow both the cameras and the audience to focus on the actors without distractions. Nothing is overwrought or overdone; it is all there simply to supplement the performance of the actors.

I would strongly urge fans of Shakespeare both old and new to watch this film. It comes across as a political thriller, giving us the opportunity to enjoy one of Shakespeare’s plots without getting side-tracked by a meditation on his language. It is populated by themes which still resonate with a modern audience, about the ease with which corruption sneaks into even the most honourable political system.